Why Prisoners Need Tech to Improve Their Post-Incarceration

It’s a big deal that Jason Walker earned his GED at age 36. Where he studied for the test—behind bars—the teachers aren’t required to have educational credentials and not all have passed America’s high school equivalency test themselves.

After eight years in a Texas state prison, in Walker’s experience learning has been disruptive and fragmented. Along with security lockdowns and facility transfers, he says even trained teachers aren’t effective “because most get intimidated by prisoners and out of fear let them do whatever they want.”

What Walker wanted to do, though, was learn. So he persevered, first with a long waiting list to get into the classroom, then in classes interrupted by unmotivated students and months of delays due to insufficient staffing. Passing the GED, a test that was overhauled, computerized, and reissued in 2014 with a success rate of just 16 percent the previous year’s figure, meant access to college courses and vocational training.

Starting in the 1990s, Charles Martin set out to develop relationships with technology companies on behalf of the Oregon Youth Authority (OYA), which manages corrections for the state’s 12- to 24-year-olds. An early success involved a relationship with the nonprofit World Possible, which developed a server with preloaded content for offline communities. RACHEL (Remote Area Community Hotspot for Education and Learning), as the device is called, carries the tagline “the best of the web for people without internet” and offers access to educational resources like TED Talks, Wikipedia, and Radiolab.

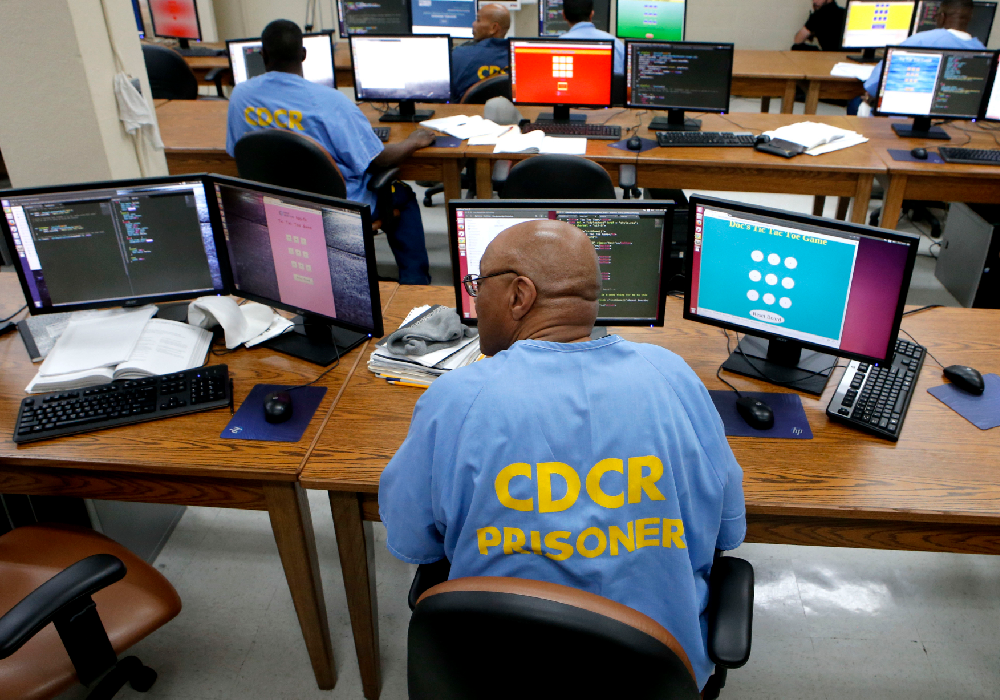

Martin also built relationships with Intel, Google, and the startup Endless OS Computers to get free software and low-cost hardware. Many schools within OYA facilities have computer labs with Google devices and open-source educational apps.

Today, Martin and his Google partners are particularly excited about the potential of virtual reality to stimulate education. Virtual welding is already on offer at MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility, an all-male prison that houses offenders between the ages of 13 and 25 in northwest Oregon. Vocational instructor Ken Perine and his student Deven say that this system decreases the time it takes to achieve welding certificates by 30 percent.

OYA was also the first corrections agency to formalize student access to email and the internet for educational and employment-related purposes, Martin says. Students have carefully restricted and monitored access to the web for their studies, which is highly unusual in U.S. prisons. They can also take classes on coding or refurbishing broken devices.

While feedback is mostly anecdotal, administrators report reduced incident rates following the introduction of educational technology several years ago. It’s also common for the students to mention the computers before any other aspect of school.

Overall, the United States lags behind other countries in getting its prisoners learning. While New Zealand is aiming for nationwide access to preselected educational websites in its prisons, Belgium’s PrisonCloud system integrates administrative tasks with internet accessible within prison cells. Another unconventional initiative, taken up in Brazil and Italy, shaves days off an inmate’s sentence for each book he or she reads.

Meanwhile, in terms of vocational education, country performances are mixed. China, which has the world’s second largest prison population after the United States, has historically focused on labor rather than education in its correctional facilities. Vocational education is often tailored to local contexts, which means Canadian inmates learn to use chainsaws while Ethiopian inmates take tourism workshops.

When Hodas and the Vallas Group, the consultancy he worked with on the DOJ assignment, looked for a viable, more flexible and engaging educational experience compared to the one offered in U.S. prisons today, he wondered, “What kind of technology platform makes the most sense?” Ultimately, he concluded, “Tablets have the best risk/benefit scenario.”

The Economist notes that America’s judicial system largely cuts off its detainees from accessing the internet and the host of educational resources it provides. As an antidote, companies like Edovo and JPay, a behemoth of private service provision to prisons, have distributed thousands of tablets loaded with educational and entertainment content but with security measures specifically designed for correctional facilities.

Edovo is a social enterprise; its tablets, which have a Learn & Earn section with GED and college coursework, vocational videos, and ESL content, get signed out on loan to interested inmates who can log in with a specific username and password. The tablet’s programming is designed so that as a user completes educational or job-based material—digestible at any pace and at whatever skill level desired—he or she earns points toward certificates, as well as ones that unlock entertainment content such as movies and music in a Play & Spend section.

Meanwhile, JPay’s tablets are part of the high-fees model that has made the prison service provider profitable: The JPay mini tablet has similar content, costs about $70, and is marketed to a prisoner’s family or friends to purchase—with recurring costs to send emails and videos back and forth as inmates plug in to connectivity kiosks under supervision.

Within prison education, the corporate presence can be murky. Since the private sector drives so much edtech innovation, there will always be a mix of private and public provision, says Hodas. Martin acknowledges the same, adding that in addition to corporate social responsibility, technology companies are also motivated by the desire to increase take-up of their products and collect data about usage.